Adieu Danny Smiřický

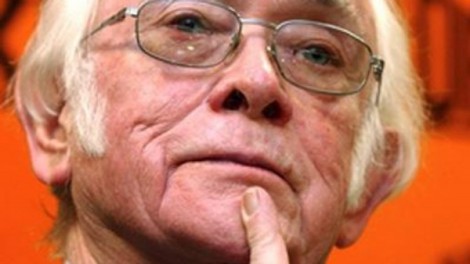

Czech emigre writer Josef Skvorecky, who published the works of former President Vaclav Havel and other authors persecuted by the communist government at home, died of cancer in Toronto on Tuesday aged 87, Czech and Canadian media reported.

Snímek PETR HLOUŠEK

Josef Skvorecky and his author wife Zdena Salivarova set up the Sixty-Eight Publishers in Toronto after leaving Czechoslovakia in the wake of the 1968 Soviet invasion that crushed hopes of the Prague Spring reforms. He published 227 titles in total.

Skvorecky’s death comes after fellow leading lights of the Czech artistic anti-communist generation also died in the past year. They include Havel, who died in December, as well as authors Ivan Martin Jirous, Arnost Lustig and Jiri Grusa.

Books published by Skvorecky were often smuggled back into Czechoslovakia, opening cracks in the heavy censorship that strangled free expression in the 1970s and 1980s.

It was nice that the books were published in Czech, beautifully done, then smuggled here for thousands of people to read, said Ivan Klima, himself a censored fellow writer. They (Skvorecky and his wife) sacrificed their own writing to that. Skvorecky was an excellent author, he told Reuters.

Skvorecky won a series of literary awards as well as the Order of Canada and the Order of the White Lion, the highest Czech award he received from Havel. He taught literature at the University of Toronto until retiring in 1990.

His first novel was The Cowards, written in 1948-1949, describing the atmosphere of Skvorecky’s native Czech town of Nachod during the 1945 liberation from Nazism.

Because it strayed from how the communist government would have liked the period portrayed, it was only published in 1958, and then anyway confiscated and banned. It was later translated into more than 20 languages.

Skvorecky’s saxophone-playing, jazz-loving alter-ego Danny Smiricky appeared in other works as well, including The Republic of Whores, an often comical description of military service in a communist force preparing for a war with the West.

Other works include The Swell Season (1975) and The Engineer of Human Souls (1977).

Skvorecky also attracted film makers. His works, including original screenplays, contributed to the successful period of Czechoslovak cinema in the 1960s and drew large crowds after the fall of communism in 1989.

Reuters, Jan 3, 2012 – 1:20 PM

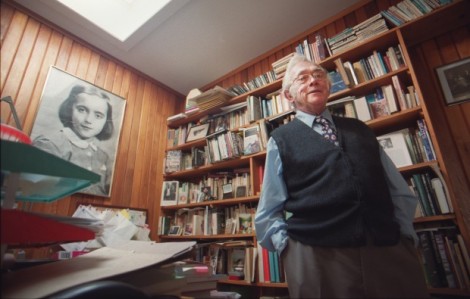

Josef Skvorecky in his office in his Toronto home, 2000. Snímek GLENN LOWSON

Josef Skvorecky: The Art of Fiction No. 112

Interviewed by John Glusman

A native of Nachod, a small town on the northeastern border of Bohemia—the westernmost part of Czechoslovakia—Josef Skvorecky has experienced virtually every major political system of twentieth-century Europe: liberal democracy under the nation’s first and second presidents, Tomas Masaryk and Eduard Benes, until the Munich Pact of 1938; Nazism from 1939 until the Potsdam Conference of 1945; “uneasy” democratic socialism until the Communist coup d’état of 1948; Stalinism until 1960; the liberalization of Communism until 1967, culminating in Alexander Dubcek’s Prague Spring of 1968, and terminated by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August of that year.

The son of a bank clerk and chairman of the local Sokol Gymnastic Association, Skvorecky graduated from the local realgymnasium in 1943, worked for two years in the Messerschmitt munitions factories in Nachod and Nove Mesto under the Totaleinsatz scheme, and was then transferred to the Organization Todt for trench-digging duty, from which he defected. For the last two months of the war he worked in a cotton mill.

He subsequently studied for a year at the Medical Faculty of Charles University in Prague, but transferred to the Philosophical Faculty, graduating in 1949 and receiving a Ph.D. in American philosophy in 1951. After teaching for two years at the Social School for Girls in Horice v Podkrkonosi, Skvorecky was drafted into the army where he served with the elite tank division stationed in the Mlada military camp near Prague, now the headquarters of the Soviet occupation army.

In 1948, at the invitation of the literary and art critic Jindrich Chalupecky, he became a member of the Prague underground circle of Jiri Kolar, and, as a frequent visitor to meetings of the Prague surrealists at the apartment of the artist Mikulas Medek, he was introduced to the underground litterateurs of the early 1950s.

An aspiring tenor saxophone player, Skvorecky began writing at an early age, but time and again political circumstances thwarted the publication of his works in Czechoslovakia. His first novel offered for publication, The End of the Nylon Age, was banned by the censors before publication in 1956. His second novel, The Cowards, which he had written ten years earlier, was published in 1958, but became the pretext for a cultural purge by Stalinist members of the Communist Party. As a result, Skvorecky lost his job as editor of the magazine World Literature, and was unable to publish until five years later, when the novella, The Legend of EmökeEmöke (1963), appeared. Though criticized by the Party, became one of the major publishing successes of the mid-sixties in Czechoslovakia. Skvorecky was still closely watched, and yet another novel, Miss Silver’s Past, was banned before its publication in 1967, only appearing afterwards under Dubcek in 1968. Not until 1967 was Skvorecky made a member of the Czechoslovak Writers’ Union, and then only because of his position as Chairman of the Translators’ Section.

With the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Skvorecky and his wife Zdena, a singer, actress, and novelist (Summer in Prague, 1973), left for Canada, where he now teaches film and American literature at the University of Toronto. His works published in Canada include two books continuing the adventures begun by Danny Smiricky in The Swell Season (1974) and The Engineer of Human Souls (1984), which won the Canadian Governor General’s Award for Fiction in 1984. He is also the author of a novel about army life, The Tank Corps (1971), a series of detective novels, including The Mournful Demeanor of Lieutenant Boruvka (1966) and The End of Lieutenant Boruvka (1975), short stories, screenplays, essays on the Czech cinema, and translations from English into Czech of Ray Bradbury, Raymond Chandler, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, and Henry James. In 1971 he and his wife founded Sixty-Eight Publishers in Toronto, now the most important Czech-language publishing house in the world. Since then they have published more than 150 books, among them new works by leading poets, playwrights and novelists such as Milan Kundera, Vaclav Havel, and Ludvik Vaculik.

Skvorecky’s most recently published work in English is (1987). Dvorak in LoveHis The Miracle Game, which was written in 1972, is to be published in early 1990. He is currently at work on The Bride from Texas, a novel about the role of Czech-Americans in the Civil War, whose life stories, he admits, may not be important historically, but they make for good fiction.

A natural storyteller who brings a special Old World sensibility to life in the New World, Skvorecky has become a satirist by circumstance, a dissident out of necessity, and has emerged as one of the most important voices in contemporary world literature. His work is distinguished by its far-reaching historical consciousness and sense of social engagement, an irrepressible wit, and a long-standing concern with human rights.

In 1980 Skvorecky was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and on presenting him to the jury, Arnost Lustig, a fellow Czech émigré author, wrote: In a country that has not had any democracy for over forty years now, books like those of Josef Skvorecky have become forbidden fruit on the one hand, and a hope for dignity and freedom on the other. Taken together, his works constitute a highly artistic presentation of recent Czech history as the common intelligent people saw it and felt it.

A man of warmth and generosity, Skvorecky chooses his words carefully, speaking in a low, gravelly voice, a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. Like many Czechs, he has a fondness for beer, which we drank to the strains of contemporary Czech jazz, while conducting this interview over two sessions in New York City and Amherst, Massachusetts.

Asked on one occasion about the meaning of one of his works, Skvorecky replied in the words of Veronika, the sad heroine of The Engineer of Human Souls: Let’s leave it to the horses to figure out. They have bigger heads.

INTERVIEWER

How old were you when you first tried your hand at fiction?

JOSEF SKVORECKY

When I was a boy, I was something of a sportsman. I played soccer, and I skied, but then I fell ill with pneumonia, which in those days was a serious disease. I almost died of it, and I was afterwards forbidden to play sports. So I became a sheltered child, and got interested in writing. I was especially interested in an American writer by the name of James Oliver Curwood, who wrote romances. Towards the end of his life he started a trilogy about trappers, but he died before finishing it. He was very popular in Czechoslovakia, and I decided to finish the trilogy for him. I wrote The Mysterious Cave as the third volume of his trilogy when I was about nine.

INTERVIEWER

What was the first novel you completed?

SKVORECKY

It was a story about student life I wrote right after my matriculation in the gymnasium—about an affair I had with a schoolgirl. My second unpublished novel was An Inferiority Complex, again a love story based on real experiences, which in a way prefigures The Cowards. My first real novel was The End of the Nylon Age, which I began writing in the university. It’s about a student who has an affair with a shopgirl, and then an actress, and gets involved in smuggling. It was important for me as a writer, because I found I was good at lyrical description—which is easy if you’re at all talented—but writing dialogue was something else. Remember, my formative years were spent under the Nazis, when access to good literature was restricted. Many books were simply banned.

INTERVIEWER

What books did you have access to?

SKVORECKY

The Czech classics, which one had to read, and therefore hated. Czech fiction didn’t really come of age until the 1930s; poetry had been the primary literary form until then. The first genuinely good Czech fiction writer was Jaroslav Hasek, a genius who didn’t have any schooling, but wrote The Good Soldier Schweik in the early 1920s. It was his one great novel; its greatness is not as a novel, but as an observation of life in a very original, personal, and caustic style. Hasek was atypical. After Hasek come Vladislav Vancura, a highly sophisticated stylist, Karel Capek, a very good short-story writer who gained renown because of his plays, and Polacek, a Jewish-Czech writer who has never been translated into English and whom I really love—a master of the language.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have any other literary influences?

SKVORECKY

Well, this shopgirl I was in love with was a real influence because she was very talkative, and she talked in scenes—literally using “scenic method.” She couldn’t tell a story in any other way: And then I said to him . . . and he said to me . . . And she also used contractions which I tried to imitate in my novel. One of the scenes from The Nylon Age, “A Babylonian Story”, is just such an experiment in dialogue. But the novel itself is probably unreadable.

INTERVIEWER

Why was writing dialogue so difficult for you?

SKVORECKY

There’s this tradition in Czech literature that books are sacred, and therefore the language used in writing books is very formal—without contractions, distortions, or slang. The Czech expression for correct language is spisovna cestina, which means bookish Czech, and it’s not a derogatory term. Most of the Czech books I was able to read were in this formal manner, and I was brought up thinking that’s how books were written.

INTERVIEWER

What changed your perception?

SKVORECKY

Hemingway. I suddenly saw that you could write dialogue as people spoke it. But I didn’t read Hemingway until the end of the war in an English-language Swedish edition of A Farewell to Arms. And then I read everything. It opened my eyes. I realized that you could write dialogue that need not be informational; it simply was.

INTERVIEWER

How were you first introduced to American culture in Czechoslovakia?

SKVORECKY

Seeing Judy Garland’s movies. I saw Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry with Mickey Rooney, in which Judy sang “Stormy Weather.” I was determined to write her a letter, so I had to learn English. The two languages everyone had to learn in Czechoslovakia were German and French, but instead of studying French, I studied English. I wrote Judy Garland that letter, but I never heard back from her.

INTERVIEWER

What was the first work you read in English?

SKVORECKY

My English teacher loaned me some of her books, and the first was Kipling’s The Jungle Book. After that came Shaw, Wilde, and Galsworthy; plays are easy to understand because of their relatively simple sentence structure. I also started listening to the BBC, which was jammed except for the English news; the announcer enunciated slowly, clearly, and with precise pronunciation, which was easy to follow.

INTERVIEWER

The period of the Soviet occupation of Prague beginning in May 1945 is also the time frame of your novel, The Cowards. How did you feel about the Communists moving in after six years of Nazi rule?

SKVORECKY

I was very concerned. My father was a committed Democrat who mistrusted both the Nazis and the Communists, and was arrested by both. I grew up believing that the Communists were not much better than the Nazis. I had an aunt who was Jewish, and also a Communist. You know, my father used to say, she’s really very nice, but she’s a Bolshevik. She was very pretty, had red nails, smoked cigarettes from a long holder, and wore pants, which in those days was considered very radical. She disappeared in a Soviet labor camp, so when the war was over, I felt that the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia was not much better—and possibly just as bad—as Nazi rule.

INTERVIEWER

Was there a widespread feeling that Czechoslovakia had been sold out by the West at Yalta?

SKVORECKY

Yes. It would have been perfectly easy for the Americans to take Prague, establish their presence, and then withdraw. But then the Americans would have been regarded by the Soviets—and the rest of the world—as Czech liberators, and the Soviets didn’t want that. And nobody wanted another war.

INTERVIEWER

When the Communists assumed power in 1948, the official aesthetic became socialist realism, though as Milan Kundera pointed out, it was impossible to be realistic.

SKVORECKY

That’s why I never even thought of submitting The Cowards for publication then. I always compared so-called socialist realism with the American western, because they are the same types of formulaic fiction. The original western, for example, features a ranch, a band of desperadoes stealing cattle from it, a local sheriff who’s an incompetent, and a stranger who appears out of nowhere. The stranger is fed up with the desperadoes, and decides to take care of them himself, which he does. He also winds up marrying the daughter of the ranch owner, and off they go together into the sunset. Compare that to the socialist-realist novel: here there’s a collective farm, a band of saboteurs or lazy workers slowing down production, local authorities who are incompetents, and a Party Setetzty from the district capital who appears out of nowhere. He exposes the saboteurs and saves the farm. Then he marries the local school teacher, and off they go together for someplace else. It’s the same formula, and I even tried my hand at it when I was around fifteen.

INTERVIEWER

What impelled you to do so?

SKVORECKY

My sister Anna had an admirer who worked for a penny-dreadful weekly, Rodokaps/Pocketnovels, which published westerns. Because he spent so much time hanging around my sister, he sorely needed someone to write up some stories for him. When he heard of my literary aspirations, he gave me some synopses, which I embellished, he reworked, and then we split the profits fifty-fifty. When socialist realism later came along, I realized it was basically the same thing. I never took it seriously and it’s never really been defined. To write truthfully and realistically, while never forgetting the bright future when it doesn’t exist, what does that mean? It’s a propagandist formula.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve described the technique of The Cowards as “magic realism,” but clearly you have something else in mind than the magic realism, say, of Gabriel García Márquez?

SKVORECKY

The end of the war was my inspiration for The Cowards, which takes place from May 4 to May 11, 1945. You see, the last days of the war in Kostelec—which probably saw some of the last fighting of the war in Europe—were really very exciting. It was the first time I experienced real danger, and I wanted to recreate that period of my life and make it, simply, magical. In Márquez, magic realism means combining the real and the surreal, which is no longer traditional realism. But the term was coined long before Márquez in Czech literary theory by the poet Josef Hora, who suggested that prose should be made as magical as poetry through the use of language and its association; so that, in Hemingway’s terms, it would be truer than truth. That’s what I aimed to do in The Cowards, which I began in the fall of 1948, and finished in the summer of 1949.

INTERVIEWER

Would you consider yourself a political writer, or a writer who’s become political by force of circumstance?

SKVORECKY

If you live in a country where politics are oppressive and you write—or try to write—you can’t avoid being a political writer. I enjoy writing about other things, but to write a novel about Bohemia in the past forty years and avoid politics entirely would be to write some sort of romantic idyll that never existed. I consider myself a realistic writer; it’s unfortunate that one becomes a political writer out of necessity.

INTERVIEWER

Aside from the implications of your writing, then, what were your political commitments?

SKVORECKY

I really wasn’t involved politically, and I don’t see The Cowards as a political novel. It certainly wasn’t intended as such, though it’s about a historical event. I was interested, simply, in how things were, and in capturing those events faithfully on paper. The main criticism was that it wasn’t political enough, that when everyone was supposed to be fighting the Nazis, the characters in my novel were interested in jazz and girls. That was considered reactionary. So the novel was attacked officially on the grounds that it distorted reality.

INTERVIEWER

But there are parts of The Engineer of Human Souls that depict overtly political acts—for example, the attempt at anti-Nazi sabotage in the Messerschmitt aircraft factory.

SKVORECKY

Of course, because that was true, too. But Americans don’t realize that Nazi rule between 1939 and 1945 differed from one country to another. In Bohemia it happened to have been relatively mild. Bohemia was a heavily industrial area with major armament factories. The Nazis needed the Czech working class to maintain production of the Skoda three-purpose guns, the Panzerjager armored attack vehicles, and other fruits of Czech technical inventiveness. Therefore, persecution in Bohemia was not as arbitrary as it was in Poland, an agricultural country with no industry to speak of. Being in Central Europe, Bohemia was also far from the front, so life had the appearance of being more or less normal.

INTERVIEWER

That is, if you weren’t Jewish.

SKVORECKY

Of course, because Jews were transported. Many Czechs were arrested, too, and when SS Obergruppenfuhrer Reinhard Heydrich, appointed protector of Bohemia and Moravia in 1941, was assassinated by Czech paras from England in May 1942, Hitler wanted to shoot every tenth Czech. Five thousand were executed in three weeks. The villages of Lidice and Lezaky were obliterated. While The Cowards was not intended to be an anti-Nazi tract, it was meant to be a realistic novel. So that portrayal did include anti-Nazi activities.

INTERVIEWER

How did you end up in the tank corps?

SKVORECKY

The army was seeking political information about various people, including my father. It so happened that my father’s barber had joined the Party out of fear, and when questioned about my father, praised him greatly as a progressive, which landed me in the elite tank corps, which I’ve described in a novel by that name, not yet translated into English.

INTERVIEWER

What was army life like?

SKVORECKY

The Czech army was slavishly modeled on the Soviet army. First-year soldiers were not allowed to leave the barracks at all. That may make sense in Russia, where most of the army bases are in the middle of nowhere, but I was stationed in the Mlada military camp, about twenty miles east of Prague. We weren’t permitted to leave that camp for a whole year, which made it more like jail, and also bored us to death.

INTERVIEWER

Were you able to do any writing?

SKVORECKY

I wrote several novellas, one of which was called The Viewer in the February Night, about the Communist takeover.

INTERVIEWER

What did you do on your release from the army?

SKVORECKY

I got a job in Prague at the state publishing house where I worked in the American literature department, specializing in fiction.

INTERVIEWER

What did that work entail?

SKVORECKY

I was a junior editor and I had to check punctuation and grammar, edit translations, and read new American and English works to recommend for translation.

INTERVIEWER

So you were working in a Czech publishing house without being able to get published yourself in Czechoslovakia. Did any of your work appear as samizdat?

SKVORECKY

No, there wasn’t any samizdat in Stalinist times. I was part of an underground literary circle, though, presided over by the poet and artist Jiri Kolar, which included the writer Bohumil Hrabal, the art historian Vera Linhartova, the poet and translator Jan Vladislav, and the composer Jan Rychlik, among others. We’d discuss art, politics, literature, and read from works in progress we knew wouldn’t be able to be published given the current political situation. At one of Kolar’s meetings, Hrabal read the first version of the story that was the basis of the film Closely Watched Trains.

INTERVIEWER

What effect did Khruschev’s speech at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 and the call for de-Stalinization have on the cultural climate of Czechoslovakia?

SKVORECKY

In 1957, during the first rapprochement after Stalin’s death, we started publishing World Literature, following the lead of the new Soviet journal, Inostrannaya literatura, or Foreign Literature. By the standards of the day, World Literature was really very radical. We published the first Faulkner, Hemingway, Waugh, and Kafka. Kafka had not been particularly lucky in terms of the publication of his works in his native country. His first novel translated into Czech was The Castle, but it appeared at the time of the Munich crisis in 1939, and simply disappeared. To the Communists, Kafka was considered a decadent writer, so he wasn’t published again in Czechoslovakia until we brought out his last, unfinished story, “The Burrow.” That beautiful drawing of Kafka by the Czech painter, Frantisek Tichy, was commissioned by World Literature, and we also published an essay on Kafka by Pavel Eisner. Eisner’s essay had been translated in Italy and published in a Communist Party magazine labelled the first Marxist study of Kafka, which was very funny, because Eisner was an old Prague Jewish gentleman who had very little to do with Marxism whatsoever.

INTERVIEWER

How did you get away with publishing Waugh, a reactionary writer by almost any standards?

SKVORECKY

I thought Waugh was the best English writer after the Second World War. He’s a brilliant technician, and I think his war trilogy — Men at Arms, Officers and Gentlemen, and The End of the Battle — is the best work on the war in Europe. Well, I realized that it would be difficult to recommend Waugh for translation, but I found a review in a Polish-Marxist journal that hailed The Loved One as a satire of American capitalist exploitation, which helped convince my editor in chief that we should print it. So we had the novel translated by a friend of mine who was a fairly clumsy translator. In this translation I came across the expression “nutburger”. Now, I had heard of hamburgers and cheeseburgers, but nutburgers? So I wrote to Waugh asking him about it, and he sent back a very funny, typically Waughian letter claiming that a nutburger was a common capitalist concoction whereby the capitalists, pretending that they were giving meat to the working class, were in reality giving them nothing more than nuts!

INTERVIEWER

The publishing situation began to change as a result of the thaw, didn’t it?

SKVORECKY

Now, even Umberto Eco is published, though the first paragraph of The Name of the Rose refers to the Soviet invasion of Prague. Of course, the Czech edition omitted the reference, but at least the rest of the book was published. When Mario Puzo’s The Godfather appeared, many Czechs who read it thought: My God, this is about the Communist Party! Which makes sense, because when the Communist Party comes to power, it acts a lot like the Mafia: if you are a loyal member in good standing, everything is yours. You’re protected, even if you commit a crime. The Godfather was translated, printed and bound. Then the most Stalinist member of the Presidium of the Party read it, and tried to block its publication. But half a million copies were already in print. So instead, the Party banned all reviews, prevented booksellers from displaying it, and there was absolutely no publicity. And The Godfather sold very well.

INTERVIEWER

The Israeli novelist, Amos Oz, once said that translating Hebrew into English is like making love to a woman through a blanket. Is much lost, when translating Czech into English and English into Czech?

SKVORECKY

I think almost any language can be translated into any other, though in North America, because of an old tradition of Czech immigration, there exists a unique English-Czech dialect, which can be very funny, because the English words undergo all the linguistic rules of Czech grammar; and that’s impossible to translate into English. On the other hand, the problem with rendering English into Czech is not so much the translation, as what is deemed unfit for translation. My brother-in-law, a former political prisoner, read The Godfather first in Czech, and then in English when he came to Canada, and discovered some very revealing revisions. There’s a scene in The Godfather, for example, when Don Corleone calls a meeting of the five underworld families to propose a peace. One of the Mafiosi says: “If Corleone has all the judges in New York, then he must share them or let us others use them. Certainly he can present a bill for such services, we’re not communists, after all.” But in the Czech translation, the sentence ends: “not even a chicken scrapes the ground for nothing after all,” which is an old Czech proverb, but not quite the same in English. In Hemingway’s novel, To Have and Have Not, and in Ginsberg’s Howl, which we also published, references to “Trotskyites” were changed to “revolutionaries”. The smuggler’s boat Aurora in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novel The Sign of Four became the Naiad in the Czech translation because Aurora, of course, had been the battleship that started the Russian revolution by shelling the Winter Palace in Petrograd.

INTERVIEWER

When did the ideological climate warm up for native Czech writers?

SKVORECKY

In the late 1950s. Because I was known to Ladislav Fikar, director of the Writers’ Union Publishing House, the most important publisher of contemporary Czech literature, I was asked to submit some work for publication. I knew that The Cowards was still too hot, so I offered The End of the Nylon Age, and it was accepted in 1956. In the fifties, if an editor considered a manuscript politically “safe,” it could be set in type, and then page proofs would be sent to the censor. If, on the other hand, a manuscript was thought “controversial”, it was sent to the censor before being set in type.

INTERVIEWER

In other words, the editor acts as a pre-censor?

SKVORECKY

Exactly. Theoretically, there was no censorship in Czechoslovakia, but a “Bureau of Press Supervision”, which supposedly had no right to ban anything. It could only recommend, or withhold a recommendation, for publication. If an editor was courageous, he could still publish a manuscript not recommended for publication by the Bureau of Press Supervision, but no editor would be foolish enough to do that. So the manuscript of The End of the Nylon Age was printed, sent to the censor, and I was asked to go before the Bureau. One of the censors was a young woman around thirty who said to me: You know, comrade, we cannot recommend this for publication, because it is pornography. To which I replied: “There’s absolutely nothing pornographic in it. If there is, show me.” But she stammered and said: I can’t read this aloud, I would blush, and she wouldn’t read from the passage before her. Finally, the other censor—an older man—read it and came across what she regarded as pornographic, which was the word bosom. That infuriated me. If you want me to replace it with a folksier expression,” I said, “I can do that, too. Well, she didn’t. Instead, she threw me out of her office, and that was the end of The End of the Nylon Age. It was finally published in Czechoslovakia in 1967. I even received a prize for it from the Writers’ Union.

INTERVIEWER

How did The Cowards finally get published?

SKVORECKY

Well, Fikar wanted to try that as well, so we sent The Cowards to the censor a year later, in 1957, and to our surprise, they did not object at all. I cut this version from 800 down to 500 pages, and it was published in 1958, the day before Christmas. There was a review of it in the Writers’ Union Weekly, but since it was a first novel, and I was unknown as a published author, The Cowards didn’t sell many copies initially. It also had a protective blurb on the dustjacket that described it as “a caustic satire on the cowardice of the bourgeoisie”. Then in January, 1959, an attack on The Cowards appeared in the trade union daily, which disparaged it as a defamation of the revolution. Every day thereafter came another attack—in newspapers, magazines, and journals—and they all sounded suspiciously alike. At the time, the Stalinist section of the Party was fighting a battle of retreat, while the Liberal faction was growing stronger. The Stalinists needed an example to highlight the dangers of relaxing censorship, and The Cowards was it. I was told that originally they had selected a novel by Karel Ptacnik, The Town on the Border — which really was politically controversial — as their example, but Ptacnik was already a national prizewinner for his first novel, and moreover was a party member. I wasn’t, so The Cowards was chosen, instead.

INTERVIEWER

How did the Stalinist critique of The Cowards affect its success?

SKVORECKY

When the attacks in the press started appearing, that was a signal to booksellers that The Cowards was in trouble, and therefore would be in great demand. So they hid their copies. When a Party order was issued demanding that The Cowards be confiscated, the police went from store to store looking for it. But smart booksellers told them that The Cowards had sold out, and then turned around and sold it to their best customers at a huge profit. One bookseller told a policeman that he had had half a dozen copies, but had sold them to the Prague dairy. You see, in Communist countries there is a tradition that every enterprise rewards its best workers, and the rewards are usually books. So this is a great opportunity for booksellers to unload their unsaleable stock, like the Selected Works of Lenin. That’s what this one bookseller did with The Cowards. Copies were stamped by some party functionary who inscribed them with the names of the industrious workers and presented the books as gifts. The policeman who had visited this bookseller then went to the dairy and found out the names of those who had been given The Cowards. He was told by all the prizewinners that they had lost their copies.

INTERVIEWER

What were the repercussions of the publication of The Cowards for you?

SKVORECKY

I was under a ban, and it looked as though I might be arrested. I lost my job as an editor of World Literature, and the editors responsible for the publication of The Cowards, including Fikar, were fired as well. The Cowards became the Stalinists’ pretext for an extensive cultural purge, and they succeeded, but only for a few years. In the meantime, I soon landed a job in another publishing house. And in terms of the success of The Cowards, I couldn’t have hoped for better publicity. By 1962–63, I was allowed to publish The Legend of Emöke, one of the novellas included in The Bass Saxophone.

INTERVIEWER

Having been censured by the Party on the publication of The Cowards, what did you work on next?

SKVORECKY

After The Cowards affair, Milos Forman came to me with his wife, the beautiful Czech film star, Jana Brejchova, and said that he’d like to write a script from a short story of mine, Eine kleine Jazzmusik, to make it into his first feature film. I had known Milos since he was a boy. His parents died in a Nazi concentration camp, and Milos was raised by an uncle in Nachod, who was a grocer and a mountain-climbing buddy. He had just graduated from the Film Academy, and we decided to collaborate on the script for Eine kleine Jazzmusik, which we presented to the studio. But in those days, there was a body called the Great Dramaturgical Board which consisted of some fifty to seventy people who read all of the scripts presented to the studios. Numerous members of the Board objected to our story, which was about a group of jazz-loving students who try to stage a concert during the Nazi occupation and finally succeed. We had to write and rewrite the script, substituting sabotage for jazz, until after a year it read like any wartime story of sabotage in a German munitions factory. Then the political climate changed, and suddenly these wisemen—who wondered why the film was called The Band Has Won, because by now there was no band in it, and why it was subtitled A Musical Comedy when it was really a tragedy—allowed us to reinstate what we had deleted. After another year, we were almost back to where we had been in the beginning, and the project was finally approved. Milos was delighted. I went home that night and on the late-night news heard from some enterprising journalist that a new film, written by Skvorecky and directed by Forman, was in the works. As the devil would have it, the President was listening to the news. He remembered my name from his attack on The Cowards — though of course he never read it—and when he heard the news of my film with Milos, he told his secretary the next morning that under no circumstances could a movie be made of The Cowards. Of course, he’d got it wrong, but no one had the courage to tell the President that it wasn’t The Cowards we’d collaborated on. So “Eine kleine Jazzmusik” was never made into a film.

INTERVIEWER

Was The Cowards ever made into a film?

SKVORECKY

In fact, Milos and I wrote a script for The Cowards in 1968. Milos was supposed to go to the States to make his first American movie, and return to Czechoslovakia to shoot The Cowards in the summer of 1969. We even found a girl to play Irena, who happened to be the daughter of the real model for Irena. But then the Russians came, and that was the end of The Cowards, too.

INTERVIEWER

What were you allowed to publish after The Legend of Emöke?

SKVORECKY

A collection of short stories about Jews in my native town, called The Menorah; The Babylonian Story, a selection of short fiction that included The Bass Saxophone; and the Lieutenant Boruvka detective stories.

INTERVIEWER

From The Bass Saxophone to The Swell Season, to The Engineer of Human Souls, and now Dvorak in Love, one thing that comes through loud and clear in your work is your love of music.

SKVORECKY

Well, I always wanted to be a jazz musician, and was really never much of one.

INTERVIEWER

How did you first get turned on to jazz?

SKVORECKY

There was a Chick Webb recording called I’ve Got a Guy, which featured Ella Fitzgerald. At the time I didn’t know it was Ella, because most records then didn’t list the names of the singers; the showcase was the band. That was around 1938, when Ella was twenty. I’ve Got a Guy also had a wonderful saxophone chorus, and when I heard it for the first time, I thought I was listening to the music of the heavenly spheres, and I still think that.

INTERVIEWER

But tenor sax, not the bass, was your instrument. When did you first get one?

SKVORECKY

In the gymnasium a student who was five years my senior, and the son of the editor of the local paper, started a jazz band. After hearing Chick Webb, I started going to their rehearsals, which featured a brilliant trumpet player who appears as Benno in The Cowards and The Swell Season. I convinced my father to buy me a tenor sax, and then we started our own band, Red Music, which I describe in The Bass Saxophone. I realized quite quickly, however, that I wasn’t gifted enough to be a professional musician. Also I had problems with the breathing, having suffered from childhood pneumonia.

INTERVIEWER

Was the story of The Bass Saxophone based on a real incident?

SKVORECKY

There was no bass sax player in town, but a friend of mine was forced to replace a German saxophonist in a German band in Nachod, and he told me how embarrassed he was about the experience. That became the historical basis of the The Bass Saxophone. The primary inspiration for the story, however, was literary. Though The Cowards was seen, in its day, as a break from socialist realism, in the 1960s, with the introduction of writers such as Kafka, Beckett, Ionesco, and Robbe-Grillet, I was viewed as something of a traditional realist, and therefore no longer in vogue. The idea for The Bass Saxophone came to me one day when I was ill and at home, and I wrote it, really, as an aesthetic statement, not at all in the vein of realism.

INTERVIEWER

The acceptance of The Bass Saxophone, a work about the triumph of art over politics—a risky proposition from the point of view of socialist realism—attests to a more liberal cultural climate. Do you feel now, twenty years after the fact, that the Prague Spring of 1968 and the events leading up to it have been accurately represented in the historical literature?

SKVORECKY

There was certainly a thaw before the Russians came in that August, but I also feel that it’s been idealized, and was not nearly as glorious as it now appears. There were still constant battles with the censor. For instance, I wasn’t even accepted by the Writers’ Union until 1967 because I was considered a suspicious character.

INTERVIEWER

Were you able to attend the Fourth Writers’ Congress in 1967?

SKVORECKY

Yes, but only as a representative of the Translators’ Section, not of the Writers’ Union. When I was elected Chairman of the Translators’ Section in 1967, I automatically became a member of the Writers’ Union, entering, so to speak, by the back door. Remember, also, that I really hadn’t published very much in Czechoslovakia. When I wrote Miss Silver’s Past and offered it for publication in 1966, it was first rejected, then accepted by the publishing house of the Youth Union, rejected again when their editor in chief was fired, and finally published only under Dubcek in 1969, although a second printing of 80,000 copies was destroyed in 1970. When a chapter of The Tank Corps was printed in a literary monthly, appearing, seemingly by coincidence, on Army Day—a Czech holiday—the political commander of the army forbade any Czech magazine from printing any kind of satire on army life in the future. But I wasn’t the only one having difficulties; those involved in the new wave of Czech film had terrible problems.

INTERVIEWER

When did you sense the beginning of the end of the Prague Spring?

SKVORECKY

Very soon, beginning, actually, with the relaxation of censorship. Dubcek announced that though censorship had been removed, judgment should be exercised, and that was simply naive. Once censorship is abolished, you can’t suppress the urge of journalists to write. And a state such as Czechoslovakia just couldn’t tolerate that. For example, everyone believed that Jan Masaryk, the son of the first president and chief founder of Czechoslovakia, Tomas Masaryk, had been murdered by the KGB after the Communist putsch of February, 1948. The official party line, however, was that it was suicide, though a man who owns a gun, and has access to sleeping pills and poison, doesn’t jump out of his second-story window if he wants to kill himself. Yet it was taboo to print such a deduction. Then Ivan Svitak, I believe, wrote an article about Masaryk’s death alleging that Masaryk was not a victim of suicide, but instead had been murdered by Beria’s gorillas. Well, other journalists followed with their own theories, after their own research, and then there was a string of sudden deaths. The secret police couldn’t withstand such a challenge to its authority. You cannot have a member of the Warsaw Pact that suddenly becomes freer and more democratic than democratic nations in the West. So I knew that the period of the so-called Prague Spring would end in disaster; it was only a matter of time.

INTERVIEWER

Prague Spring seems to have been largely an intellectual revolt. What role did the workers play in it?

SKVORECKY

It was triggered by writers and intellectuals, but it had mass support in the general populace. Dubcek was genuinely popular, the only Communist leader in Czechoslovakia to be so. Before Dubcek, marching through the city on May Day was mandatory. But in May 1968, it was absolutely spontaneous, and by far the greatest manifestation of support for Dubcek. Revolutions are never started by the masses; they always have an intellectual head, which is not to say that the Czech populace is not an extremely well-educated one. There was a tremendous amount of enthusiasm during the Prague Spring—and I shared that—but I knew it couldn’t last.

INTERVIEWER

Do you in any way blame Dubcek for a lack of leadership, or for underestimating the chances of Soviet intervention?

SKVORECKY

He was a very weak leader. Remember Goethe’s poem, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice? Well, what happened to Goethe’s apprentice once he was left to his own devices by the wizard, is what happened to Dubcek. He started a mass movement that he simply could not control.

INTERVIEWER

When did you leave Czechoslovakia?

SKVORECKY

I was in Paris with my wife when the Soviets entered Prague, and when I heard the news I didn’t want to return, because I knew this was the end. Zdena was a student at the Academy and wanted to continue her studies. She convinced me to return in October, 1968, but after three months, she realized how terrible things were, so we left for Canada, where we’ve been ever since.

INTERVIEWER

At the Fourth Congress of the Writers’ Union, Ludvik Vaculik was quoted as saying: Freedom exists only in places where one does not need to speak about it, a sentiment echoed in The Engineer of Human Souls. How has your new-found freedom in Canada affected your work as a writer?

SKVORECKY

In my eighteen years in Canada, I’ve written more books than I did as an adult writer in more than twenty years in Czechoslovakia. There’s no censorship here, and as a result, you know that if you write something good, there is the opportunity to publish it. In Czechoslovakia, you can write a masterpiece, and there’s no guarantee that it will ever be published.

INTERVIEWER

Were the actual conditions under which you wrote in Czechoslovakia inhibiting for a writer? In other words, to paraphrase the theme of the 1986 PEN International Congress, how did the imagination of the State affect your imagination as a writer?

SKVORECKY

Very much. In my first ten years of serious writing, beginning with the end of World War II, I wrote for my desk drawer only, without any hope of being published given the political situation. But when you reach a certain age, you want to see yourself in print; otherwise, it becomes oppressive. You can’t continue to write for the desk drawer until you are sixty. Even Kafka saw some of his works in print. But writing remains a potentially dangerous act. When The Stories of the Tenor Saxophonist, which I wrote in the 1950s, fell into the wrong hands, I was threatened with exposure. And then you could go to jail for having written something, even if you didn’t try to publish it. Kolar spent a year in jail precisely because of some poems he wrote, not for publication, but which the police got hold of anyway and considered anti-State. It’s much better now, since the death of Stalin, but still the atmosphere is inhibiting.

INTERVIEWER

What are the literary merits of the officially-sanctioned literature?

SKVORECKY

In spite of what one might expect, not all of it is bad; in fact, some of the writers are quite talented. The trouble is they’re not writing up to their full potential because they can’t write freely; they have to avoid certain themes and subjects that happen to be some of the most important ones of the time. No matter how you look at literature, the fact is that great books are usually focused—in one way or another—on the issues of the day. In the America of the Depression, for example, you had Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, because that’s what America—or at least a part of it—was living through. But in Czechoslovakia, which is a police state, everything is under control to a certain extent. So how can you write a great novel if you cannot touch upon the most burning issues of the society of which you are a part? Let’s face it, all writers are ambitious and like to see themselves in print, and that leads many talented writers to compromise in such situations; otherwise they will never be published. Nowadays it’s a little easier, because dissident writers can be published abroad, but who knows what may happen next, internally? Writers such as Vaculik, Vaclav Havel, and Ivan Klima, among others, have been living under the conditions of a ghetto—of police surveillance and isolation—for years. It’s a miracle they’re able to produce anything. In the western world, by contrast, all you have to worry about, really, is your talent. And the competition! The freedom here is not a four-letter word; it’s real. Because when it doesn’t exist, you know it, and I’ve known it.

INTERVIEWER

In fact, what Milan Kundera called your magnum opus, The Engineer of Human Souls, was written not in Czechoslovakia, but in Canada, though the narrative constantly shifts from the East to the West, from the Old World to the New. How did you conceive of that structure, which was a significant departure for you in terms of technique?

SKVORECKY

I had so much material—really the accumulation of a lifetime—that the problem with The Engineer was how to organize it and incorporate it into a traditional novel. I decided instead to try to imitate the way life appears in this chaotic twentieth century where we are bombarded by disparate experiences and impressions. I thought that the structure of the novel should reflect the collagelike nature of our time. The idea really came from our flight from Czechoslovkia. The day in 1969 that Zdena and I left Prague for good was just after the funeral of Jan Palach, the student who immolated himself in protest over the erosion of freedoms in Czechoslovakia. Prague was dreary and gloomy, and there was a foreboding of bad tidings to come. But in less than an hour’s flight, we arrived in London’s Heathrow airport on a bright, sunny day, where we ran into these happy English tourists apparently returning from their vacation in the Alps. It was an incredible difference of mood, place, and character. Because of this disparity, I felt that the proper form for a modern novel would be to write it in conflicting, collagelike scenes—the “deliberate confusion” of Conrad’s psychological realism—which is what I did. I wrote the episodes separately, and then wove them together to create a sense either of contrast or continuity.

INTERVIEWER

It’s interesting that you describe the composition of The Engineer in visual terms, of “collagelike scenes”, while the structure of the novel impressed me as being closer to the musical term of counterpoint.

SKVORECKY

Well, you’re right. That’s really a more accurate description, because the episodes are interwoven as themes.

INTERVIEWER

Had you ever experimented with that technique before?

SKVORECKY

The first book in which I attempted this was Miracle in Bohemia, where I introduced an episode at the very beginning and reintroduced a similar one at the very end to bring it full circle.

INTERVIEWER

Isn’t that part of Poe’s dictum in The Philosophy of Composition where he said, referring to The Raven, that “all works of art should begin at the end”?

SKVORECKY

I knew with The Engineer that I would end up with one of the same characters who opens the book, Lojza—a character so simple that he’s virtually unchanged from one political system to the next, and yet he’s happy, whether under the Nazis or the Communists. Of course, the other characters undergo a lot of suffering, changes of heart and conscience, but Lojza has no problems whatsoever.

INTERVIEWER

In the very last scene of the novel, Danny receives a letter from Lojza in Czechoslovakia, who informs him, in broken English, that he’s become a writer, too—in other words, a real “engineer of human souls”, as Stalin defined the role of the writer under socialism. And that leads right back to the novel’s beginning.

SKVORECKY

Yes, because that’s what Danny could—or would—have become had he continued living in Lojza’s society. All you need to do is close your eyes, toe the party line, and you can be successful. But Danny’s an “engineer of human souls” of a different sort in Canada. He also writes about workers, but of course they’re not presented in the light in which they’re supposed to be seen according to socialist theory. In fact, one Czech critic writing in a Parisian literary quarterly saw the factory girl, Nadia, as the first really good portrait in Czech literature of a proletarian girl.

INTERVIEWER

The sobering historical experience of which you write in The Engineer of Human Souls is redeemed by an irrepressible and irresistible Skvoreckian sense of humor, which operates at two removes from reality. Not only does Danny Smiricky look at the world in a humorous light, but that becomes the light in which you view him as well.

SKVORECKY

Yes, and humorous writers tend to be sad at heart.

INTERVIEWER

Humor is also a defensive weapon, and one that is used to break down barriers. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Kundera’s first novel was called The Joke.

SKVORECKY

Humor has always been something of a defense. Is there an aristocratic humor that originates with the aristocracy? I don’t think so. But there is a black humor, a Jewish humor, even a humor that arose at the time of the nuclear accident at Chernobyl—a time of immediate and dangerous threat. My question is, where do such jokes come from? You always hear: Did you hear the one about . . .?, but no one seems to remember the ultimate source. Which reminds me, did you hear the one about Reagan’s and Gorbachev’s bodyguards?

INTERVIEWER

No.

SKVORECKY

Well, Reagan and Gorbachev are having a dispute about whose bodyguard is more reliable, so Reagan calls in his bodyguard and tells him: “Look here, we’re on the thirty-fifth floor, there’s an open window, so run and jump out of it.” And the man falls to his knees and says: Oh, Mr. President, please don’t make me do that, I have a wife and children. So Reagan says, All right, let’s forget about it. Then Gorbachev calls his bodyguard, and tells him to do the same thing. So the man runs to the window and Reagan tries to stop him. What, are you crazy? the President asks. And Gorbachev’s bodyguard falls to his knees and says: Oh, Mr. President, please let me jump, I have a wife and children . . .

INTERVIEWER

Not bad, and not all that different, really, from the source of much of the humor in The Engineer — different interpretations from different historical contexts that reveal, ultimately, surprising cultural similarities. That’s made most clear in The Engineer by the literary framework you’ve imposed on your own historical experience; in the chapter entitled “Hawthorne,” for example, your discussion of Puritan intolerance in The Scarlet Letter calls to mind the intolerance of the modern Communist state, and makes a striking parallel between two seemingly disparate historical moments.

SKVORECKY

That’s true. Remember, also, that each reader brings his or her own experience to bear on an interpretation of a work of art. Many of the incidents in The Engineer involving students and their interpretations of literature were taken right out of my own classes in American literature at the University of Toronto. Hawthorne’s Blythedale Romance, for instance, means something very different to an American or English reader with only a certain kind of experience. Hawthorne was unique in that he experienced a kind of democratic socialism—albeit briefly—under the Brook Farm experiment of 1840, and he recognized the character types such a system produces. The great radical of The Blythedale Romance is a type that is not extinct. In the early nineteenth century he would have been a leader of a commune, and that type is with us to this day. So to me, The Blythedale Romance is a very realistic novel, and I think of Hawthorne as a novelist who was a realist at heart. But he lacked the necessary technique, because he grew up at a time when romantic fiction was the vogue. His realism, therefore, appears only in fragments of his novels, and in short stories such as Sights from a Steeple, a beautifully realistic sketch.

INTERVIEWER

How did you conceive of such a literary framework for The Engineer, where the implications of the writer—or work—under discussion, from Poe to Lovecraft, complement the moral and political development of your characters? In the opening chapter, for instance, we have the purest statement of an aesthetic—as formulated by Poe—and in the closing chapter on Lovecraft we have its bastardization, just as the first chapter is narrated by Danny—a free soul—and the last scene is narrated by Lojza who has also become a “writer” — of local news for a village weekly.

SKVORECKY

Well, just as the episodic nature of the novel derived from my flight from Prague to London, this framework was inspired by misinterpretations of my interpretations of American literature, or by other interpretations. For example, there is a famous study of Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage and the thesis is that it’s not so much about the Civil War as about a young man’s coming of age. Now that may be true to a certain extent, but you can’t then say that it’s not about the war, as some of my students might infer. As for Lovecraft, he’s a tongue-in-cheek prophet of doom, and in the sinister At the Mountains of Madness Danny sees a prophecy of the future of the world. When he thinks back to Irena, he thinks: “Dominus tecum.” Only God can protect her and her class from disaster. Lovecraft may not be a very good writer, but I found the part quoted from At the Mountains of Madness extremely powerful. I first read it when I returned from the infectious ward of the hospital where I had hepatitis. My friend who translated Waugh gave me a copy of Amazing Stories, which contained At the Mountains of Madness, and I started reading it at 11 p.m. while I was waiting for Zdena to return from the theater, and I was scared out of my wits.

INTERVIEWER

Most of the writers discussed in The Engineer of Human Souls are nineteenth-century Americans, with strong moral visions. Why so few modern authors?

SKVORECKY

It may have something to do with the dilution of moral issues. I would, however, agree with William Faulkner, who said in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize that there are certain values that must be upheld and propagated. Unfortunately, it seems that today everything has been so relativized, that there’s an enormous amout of hypocrisy and stupidity. Each moral question—for example, abortion—has to be questioned in its entirety—from all sides, not just one side. Many issues can’t be solved simply, and the duty of the writer is to present the complexity of an issue.

INTERVIEWER

So a writer, from your point of view, does have a moral responsibility?

SKVORECKY

Yes. Which is not to confuse morality with ideology. Ideology is alien to life; it’s superimposed on life, and does damage to it. If a writer becomes converted to an ideology and tries to apply it to his work, then he is finished as a writer. Literature should have nothing to do with ideology; when you start writing ideological novels, you are no longer a writer, but a propagandist.

INTERVIEWER

But doesn’t a moral point of view frequently embrace an ideological one?

SKVORECKY

It does. But look at Graham Greene. Greene is a Catholic writer, but he never writes a simple ideological tract. All of his novels show the complexity of a religious or political issue. In fact, to a staunch Catholic ideologue, Greene would be a heretic. There was a great Czech poet by the name of Vladimir Holan, whom I used to visit. One day, a steadfast Catholic brought up the question of Greene, and said: I am afraid Greene will not be saved because some of his novels are really heretical. Infuriated, Holan replied: I’d rather be with Greene in hell, than with you in heaven! No, I don’t always agree with Greene, but he’s a wonderful writer precisely because he approaches difficult moral issues in all their complexity.

INTERVIEWER

Your most recent novel, Dvorak in Love, is the first of your major works to be inspired by biography, not autobiography. How did its composition differ from that of your other works?

SKVORECKY

I read, first of all, everything there was to read on Dvorak, though the literature is not nearly as substantial as it is, for example, on Mozart. I visited Spillville, Iowa, a purely Czech village where Dvorak stayed during his visit to America in the 1890s. I also interviewed two one-hundred-year-old women—one who was Swiss, the other Czech—who actually knew Dvorak.

INTERVIEWER

What inspired you to write a novel about the fortunes of Dvorak in America to begin with?

SKVORECKY

The idea really came from an earlier visit to Spillville. In 1969, I had a job teaching in Berkeley, and I got an offer to go to Toronto. Since Zdena and I had two months between positions, we drove across the country. I had known about Spillville, and about Dvorak’s visit to it. It’s still a charming village, and its citizens are very proud of their Czech heritage.

INTERVIEWER

As different as Dvorak in Love is from your other works in conception, it still manages to incorporate many of the same themes.

SKVORECKY

But I have a hypothesis expressed in Dvorak in Love; namely, that Dvorak had an indirect influence on the acceptance of jazz in America.

INTERVIEWER

Didn’t the music critic Huneker make that point in Dvorak’s own day?

SKVORECKY

Yes, but in not so positive a light. When Dvorak died, Huneker wrote that Dvorak’s influence on serious American music was actually detrimental . . . that thanks to Dvorak, we might live to see the day when a drunken Negro would perform in a concert at Carnegie Hall, and that would be called music. Dvorak was impressed—and influenced—by his new surroundings and by the spirit of certain Negro melodies. If you listen carefully to the New World Symphony, which was first performed in Carnegie Hall in 1893, you can hear the strains of the spiritual Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, though the opening bars have been omitted. Huneker was the only American critic who didn’t like it, nor did he like Dvorak. A talented man who never fulfilled his own ambitions, Huneker claimed that the New World Symphony was derivative, and reflected, instead, Dvorak’s ignorance of American music.

But what’s important is that Dvorak was also a teacher. One of his students was Will Marion Cook, who was black. Cook was raised by his mother, studied at Oberlin, and received much of his musical education in Berlin. When he returned to America, he studied composition under Dvorak, and later wrote the first black musical with the black poet Paul-Laurence Dunbar. It was called Clorindy, or The Origin of The Cakewalk, and appeared in New York in 1898. In his unfinished autobiography, which his son, who still lives in Washington, D.C., showed me, Cook wrote that when his mother saw the musical she exclaimed: “Oh, Will. I sent you around the world to become a great musician, and you’ve come home such a nigger!” I’m not saying that Cook became aware of his cultural roots because of Dvorak and Dvorak only—he was, of course, part of the Harlem Renaissance—but if you remember Dvorak’s simple theory that the only way to write great music is to immerse yourself in your native music, you cannot exclude some connection here.

Cook then started his own band, the Southern Syncopated Orchestra—a proto-jazz band that featured several compositions by Dvorak, and was the second black group to tour Europe after World War I, the first being a military one. The first clarinetist was Sidney Bechet, whom Cook had heard in Chicago in 1918. Cook became a successful composer, and was a tutor of Duke Ellington, who credits Cook with having taught him the fundamentals of composition, and whose Black, Brown, and Beige, some critics believe, may have been influenced by the “Largo” from Dvorak’s New World Symphony. Through his students, some of whom became professors at the Conservatory, Dvorak may have had some influence also on such modern American composers as Aaron Copland and George Gershwin.

INTERVIEWER

Ironically then, a Czech composer may have influenced the early development of jazz in America, yet jazz has been banned in Czechoslovakia as a subversive art form.

SKVORECKY

Well, some early American reviews of jazz sound very much like Soviet reviews. The difference is that a reviewer in America has no political power; it’s simply an opinion. In Czechoslovakia, on the other hand, a reviewer does have political power, and that’s the basic difference between totalitarianism and democracy. So though jazz in America may have aroused a lot of opposition initially, in a totalitarian state, such bias becomes law.

INTERVIEWER

What is the current status of the Jazz Section in Czechoslovakia?

SKVORECKY

The government has been dead-set on destroying it. The Jazz Section was formed in 1971 as part of the government-approved Czechoslovak Musicians’ Union, and consisted of a group of jazz aficionados who sponsored lectures on jazz, staged concerts, and organized the international festival held once a year, the Prague Jazz Days. But as membership climbed into the thousands, and the Prague Jazz Days attracted thousands more potential supporters, the government saw a growing movement with a broad base of popular support and decided in 1984 to crack down on the Jazz Section. So they effectively banned it. The Section itself has claimed that its activities aren’t counter to the principles of Marxism. They even built a monument to the United Nations in the fall of 1985, around which they planted “peace trees,” two of which were planted by Kurt Vonnegut and John Updike. But in spite of this gesture, the government cracked down again. In September, 1985, seven members of the Executive Committee of the Jazz Section, including its president, Karel Srp, were arrested in Prague and charged, according to the Communist Party press, with “unauthorized business activities”.

INTERVIEWER

Meaning?

SKVORECKY

Publishing books that no official publisher in Prague would touch, such as Bohumil Hrabal’s I Served the King of England and Jaroslav Seifert’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, as well as a book on music in the Theresienstadt ghetto, a dictionary of Czechoslovak rock and roll, Nietzsche’s book on Wagner, a study of the work of E. F. Burian, the prewar communist avant-garde stage director and historian of jazz, a book on dadaism, on minimal, earth, and concept art, on New York’s Living Theater, and so on. If the trial in Prague takes place, it will be a major violation of the Helsinki accords signed in 1975.*

INTERVIEWER

Do you think Gorbachev’s decision to free Sakharov, as part of his campaign of glasnost, might have a trickle-down effect in Czechoslovakia and other Soviet-bloc countries?

SKVORECKY

That is another factor. Gorbachev is freeing dissidents, nominating a controversial writer to be the editor in chief of Novy mir, talking about electoral reform, and trying to put the Soviet system into forward gear, while Czechoslovakia is preparing to stage a show trial, reminiscent of the days of Stalin. Ironically, the Soviet Union today looks like Czechoslovakia twenty years ago during the Prague Spring, and Czechoslovkia now looks more like the Soviet Union. The Jazz Section was never intended as a political organization, but they’ve become one in response to harassment by the state.

INTERVIEWER

Once again, the state has succeeded in politicizing art. Do you feel that some American intellectuals may be guilty of the same thing, to a lesser degree?

SKVORECKY

In an open letter to Milan Kundera, Norman Podhoretz claimed that Kundera was being claimed by the left, whereas he really belongs with the neoconservatives. There is a lot of truth in this. When asked in an interview if The Joke was about Stalinism, Kundera replied: Spare me the Stalinism. The Joke is a love story. Well, The Joke is a love story, but one that’s played out under circumstances that are unquestionably political. But if someone is a good artist, like Kundera, his art will naturally transcend politics. Pound is the perfect—almost unbelievable—example, as was Celine, who was a Nazi and a great novelist. The trouble is that ideological regimes don’t respect a difference of opinion. Ideology, as Engels said, is false conscience; it falsifies reality by imposing its own structure.

INTERVIEWER

Back to your own writing: Was your satire on Army life in Czechoslovakia, The Tank Corps, finally published there?

SKVORECKY

It was written in 1954 just after my military service, and finally accepted for publication in 1968, set in type, and illustrated. Then the Russians invaded Czechoslovakia. One of their first objectives on entering Prague was to seize the building of the Writers’ Union, where the union’s publishing house was also located. The Russians occupied it for about three weeks, then withdrew, and the editors moved back in. Nothing was missing, it seemed, except for the page proofs of The Tank Corps. A few days later an editor found them in some unsuspected place, and the reason was quite obvious: the frontispiece illustration was a magnificent caricature of a group of Army officers’ faces, and apparently some Red Army soldier had found it, and penned in, under the most repulsive looking officer’s head: Eto golava prjaklyatoy svini, generala Antona Antonovitche Gretchka, which means this is the head of that fucking pig, General Gretchko. Gretchko was the commanding officer of the invading Soviet forces. This soldier had clearly gotten scared of what he had done, and he hid the evidence. So The Tank Corps was never published in Czechoslovakia. It ended up being the first publication of Sixty-Eight Publishers, the Czech-language house Zdena founded in Toronto in 1971.

INTERVIEWER

Though you can’t return to Czechoslovakia in person, are your works smuggled back there?

SKVORECKY

We estimate that about 200 copies of every book we publish make their way into Czechoslovakia, where they’re avidly read.

INTERVIEWER

Are they circulated and reproduced as samizdat?

SKVORECKY

We know they are, because we’ve received letters from people—particularly during the summer, when many Czechs go to Yugoslavia for vacation—telling us about our books, though the letters are unsigned. Whoever owns a copy really operates as a lending library, maintaining lists of subscribers, and restricting loans to forty-eight hours. The one complaint we’ve had is that our books should be published in hardcover since they tend to fall apart after 300 people or so have read a copy. But the books are also copied—though not xeroxed, since access to reproduction machines in the ministries and public libraries is closely guarded. So our books are retyped, and carbon copies are made. Ironically, they’re more intensively read in Czechoslovakia than in exile; access to books here seems to reduce interest in them. One of the reasons they’re so actively read is that magazines in Communist states are terribly boring. In Bohemia, they publish one literary monthly, and that hasn’t changed in fifteen years. They’re very big on socialist literary criticism and on state anniversaries. In 1968, when censorship relaxed, there was a sharp drop in book sales in Czechoslovakia because the daily papers and magazines were full of real news. Now, however, there’s real interest in books from abroad in Czechoslovakia, because the information they contain can’t be gotten elsewhere.

INTERVIEWER

E. L. Doctorow wrote an article in The Nation criticizing the American public’s passive acceptance of the Reagan administration’s policies; Daniel Patrick Moynihan in The New Republic diagnosed the country’s malady as ideological AIDS; and Alfred Kazin in The New York Review of Books lamented the decline of intellectual life in America. What’s your view of America from Canada?

SKVORECKY

I think Reagan’s been a good president. The American economy seems to be in better shape. He’s a traditional conservative, and he’s staunchly anti-Communist, in which sense I’m fully sympathetic to him. I don’t understand the criticism of Reagan for anti-Communist rhetoric, because this is a system that has killed millions of people. I don’t think the Reagan administration has contributed to the decline of intellectual life at all. The fact that you can have The Nation, The New Republic, and The New York Review of Books voicing a variety of opinions attests to a healthy intellectual life in America, in my opinion. Such critics should read Pravda; then they’d see where there’s a lack of intellectual life.

INTERVIEWER

Margaret Atwood has said that most Canadians look at America as if their noses were pressed against a pane of glass, while most Americans think of Canadians as either living in their backyard or front lawn, depending on where they want to put them. Do you find that to be true?

SKVORECKY

She may be right, but remember, I came to Canada in my mid-forties, and at that age all of your associations have already been made: you’re a finished product. I’m certainly not a Canadian in the sense that Margaret Atwood is, and I’ve always sensed that Canadians have a real problem with their national identity. Their main problem is the language; because they speak English, it aligns them with, instead of differentiating them from, Americans. The standard, in terms of money, career and success, also seems to be American. A Canadian actor, for example, will go to America to make it in the movies, just as the major success of many Canadians, from Fay Wray to Mordecai Richler to Margaret Atwood herself, has been in America. But America went through this same phase in the nineteenth century, when writers were judged by the fact that they were American rather than by their literary excellence or lack of it. Poe objected to this prejudice: a book should not be judged on the basis of nationality, he said, but on its merits as a work of literature.

INTERVIEWER

But you closely identify with your Czech nationality in your work even though you are now a Canadian citizen. Do you consider yourself then, a Czech writer, a Canadian writer, or a Czech writer who lives in Canada?

SKVORECKY

I suppose if you make literature dependent on language, then I’m a Czech writer, because I write fiction in Czech. I write articles in English, but one doesn’t have to be as at home in a language to write nonfiction as to write fiction. But I’m also a Canadian writer. I now write also about this country that gave me what I’d never had before: creative and political freedom.

INTERVIEWER

The Czech poet Jan Neruda has written: Even if thunder rolls and our bones freeze, it is not different from what we suffered through the ages. We will move ahead. In light of the current political situation in Czechoslovakia, is there any hope for the future?

SKVORECKY

I suppose as long as the bomb isn’t dropped, there is hope. I understand from friends of mine in Prague and Vienna that the Party bosses are criticizing Gorbachev for going too far too fast. They are afraid that, one day, they might have to invade the Soviet Union to save socialism there. But quite seriously: I don’t see how Czechoslovakia can continue on the course they have been on for the past twenty years, and ignore what’s happening in the Soviet Union. Otherwise they will find themselves in the situation of Rumania.

INTERVIEWER

How might Westerners help effect change?

SKVORECKY

Through the support of dissidents, through groups such as Charter 77, which was formed in Czechoslovakia to monitor the Helsinki accords, and by protesting human rights violations to President Gustav Husak of Czechoslovakia.

INTERVIEWER

What about more active cultural exchanges between the U.S. and Czechoslovakia?

SKVORECKY

They’re good since Americans will be able to export more art, music, and film, and it’s good for Czechs to be exposed to them since it undermines totalitarianism. But cultural exchanges won’t change much in terms of the internal political situation for Czech dissident writers, artists, and musicians who are under increased surveillance. And these people must not be forgotten, because if they are, something might happen to them, and then nobody will ever know.

INTERVIEWER

You said once that you read books as if they contain news from an old friend. What news do your books contain, and for whom?

SKVORECKY

Every writer writes, first of all, for himself. I think my primary readership consists of intelligent exiles because I write about Czechs not only in Czechoslovakia, but also in North America as in my new novel, about the role of Czechs during the Civil War. But I believe that if something has relevance for people of my own nation, then it probably has relevance for everybody, and that there’s something universal about it. The accidentals may be different, but the basics are the same, and they’re universal.

INTERVIEWER

In what way?

SKVORECKY

Well, I remember reading a book about Tutankhamen’s tomb and the discovery of his coffin. Apparently the mummy was surrounded with gold and jewelled artifacts, and on uncovering it, archeologists found on the breast of the mummy a handful of field flowers, which they theorized had been put there by Tutankhamen’s young wife. This is such a universal gesture—one that happened thousands of years ago in a foreign culture—and it’s still a token of love today. I think certain types of literature do the same thing. What happens to Danny Smiricky in my works, for example, happens to people everywhere. Circumstances may change, and they may change certain people with them, but there’s a core of human experience that remains essentially the same. That, if anything, is my message.

* This interview was conducted in 1985. The trial did take place in early 1986 and two leading members of the Jazz Section were sentenced to terms in jail. For details see Skvorecky’s Talkin’ Moscow Blues, soon to be published by Ecco Press.

Komentáře k článku: Adieu Danny Smiřický

Přidat komentář

(Nezapomeňte vyplnit položky označené hvězdičkou.)

Pavel Trenský

Byl to nejen veliký spisovatel, ale i vzácný člověk, upřímný, vstřícný, velkodušný. Po dvacet let byl morálním pilířem české emigrace. Nikoho jsem v emigraci neobdivoval více než jeho.

04.01.2012 (21.36), , Trvalý odkaz komentáře,