Divadelní noviny > Blogy Burza

Nigel Charnock

Ve věku 52 let zemřel na rakovinu, již mu diagnostikovali v červnu tohoto roku, britský performer, choreograf a režisér Nigel Charnock, s Lloydem Newsonem zakladatel taneční skupiny DV8, bývalý ředitel Helsinki Dance Company a v poslední době spolupracovník Kanaďanky Louise Lecavalierové, s níž jsme v DN 8/2012 publikovali původní rozhovor (Tanec je hledání rovnováhy), a souborů Candoco Dance Company, Ludus a National Dance Company of Wales. Charnock vystupoval několikrát i v Praze. V roce 2008 nastudoval se skupinou Nanohach vlastní choreografii Miluj mě, jež byla nominovaná na Cenu Divadelních novin, a Jana Soprová s ním pro DN 20/2008 připravila rozhovor (Láska je chemická reakce, která vyprchá). Do Divadelních novin chystáme nekrolog Niny Vangeli. Pro i-DN nabízíme – bez překladu – nekrolog jeho dlouholetého spolupracovníka z DV8 Lloyda Newsona převzatý z britského deníku The Guardian. Na http://nigelcharnock.co.uk/ můžete vyjádřit soustrat jeho rodině, spolupracovníkům a přátelům.

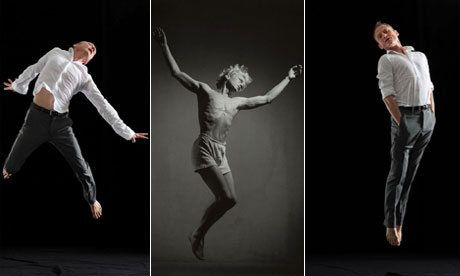

Nigel Charnock’s energy and physical commitment were overwhelming. FOTO HUGO GLENDINNING

Nigel Charnock obituary

Choreographer, director and performer who provoked and woke up his audiences

Nigel Charnock, the performer, director and choreographer, has died, aged 52, of stomach cancer. When I first saw Nigel perform at a Dance Umbrella gala in 1985, I was struck by this lithe, translucent and hyperactive creature. His energy and physical commitment were overwhelming. We met and discovered we shared disillusionment with mainstream dance and the superficiality that dominated the form. So I invited Nigel to work with me on a duet about male friendship and trust. The result was My Sex: Our Dance (1986) and the birth of the company DV8 Physical Theatre. Dancing with him remains one of the most joyous experiences of my life. He gave everything he had, emotionally, intellectually and physically.

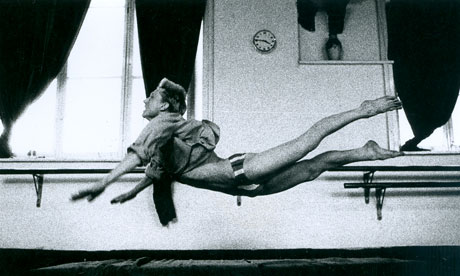

For the next six years, Nigel and I continued working together on DV8 projects. His unsparing performance in Dead Dreams of Monochrome Men (1990) and tragicomic character in Strange Fish (1992), subsequently captured on film, remain testimony to his extraordinary physicality and talent with text; he was touching, tragic, hilarious, honest.

In My Sex: Our Dance. FOTO ELENI LEOUSSI

Born in Manchester, Nigel studied at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama in Cardiff and then went on to train at the London School of Contemporary Dance (1981) before working with Ludus Dance company (1982-85) and Extemporary Dance Theatre (1985-86).

After leaving DV8 in 1993, he created a series of solos for himself: Human Being, Hell Bent, Original Sin, Resurrection and Frank, which all revolved around themes of love, redemption, loneliness and nihilism. These themes recurred through his life’s work. He formed Nigel Charnock + Company in 1995, but continued to make pieces for other companies in Britain and abroad. At the time of his death, he was working on Ten Men for his own company, an excerpt of which premiered to great acclaim at the British Dance Edition showcase in February 2012.

In recent years, Nigel was still as vital as when I first saw him. One (five-star) review of his collaboration with the jazz musician Gwilym Simcock in 2010 stated: The taut physical discipline of his fast-paced energetic jazz dance routine would have been the envy of someone half his age. In the world of contemporary dance, to have your work referred to as a „jazz dance routine“ would be considered an insult – not for Nigel. He took great inspiration from the philosophies behind jazz music and improvisation, and his later shows, the ensemble piece Stupid Men (2007) and autobiographical solo One Dixon Road (2010) were largely improvisational.

Nigel Charnock – zlobivé dítě britského tance. FOTO archiv

The only word from that review that he might have taken offence at was „dance“. Nigel had a love-hate relationship with a lot of things, but dance as a form was up there near the top of the list. He was critical of the lack of content in dance and of most contemporary choreographers, whom he believed hid behind a cloak of abstraction.

There may have been an element of defensiveness in his statements, but Nigel was scathing about the elitism of contemporary dance and ballet. He disliked arty pretentiousness: I’m more of an entertainer, I make shows, really, I make pieces, I don’t make work.

He said last year in a filmed interview: I don’t take anything seriously, oh well here we go, let’s do this – come on, you’re not here for very long, you could get cancer tomorrow, it’s only life, it’s really not important. But Nigel was a bundle of contradictions: he took many things seriously and railed fearlessly against religion, homophobia, bad hairstyles or whatever was topical that day.

In 2007, during a performance of his improvised solo Frank in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, he inadvertently caused a cultural furore by dancing on the Armenian and British flags. The Armenian minister for culture said: It is unacceptable for us that someone who is considered a national treasure to Britain would bring such low-quality art to Armenia. It was reported that some audience members likened the solo to a „strip act“ and felt uncomfortable because Nigel challenged their „conservative definitions of art“.

Thank goodness he did. I have only given a handful of shows a standing ovation. Frank, which was originally commissioned for the Venice Biennale in 2003, was one of them, and that was Nigel’s power. When he hit the spot, and usually it was with his solos, he provoked and woke up audiences – there was nothing he would not say or do. With incisive wit, he spoke aloud his private thoughts, and ours.

Nigel is survived by his two older brothers, Andrew and Peter, and his partner, Luke Pell.

Po představení Stupid Man v londýnském divadle The Place v říjnu 2008. FOTO JULIAN HUGHES

/převzato z Guardian.co.uk/2012/aug/07/, pro i-DN připravil a zpracoval hul/

Komentáře k článku: Nigel Charnock

Přidat komentář

(Nezapomeňte vyplnit položky označené hvězdičkou.)